The Popular Mechanics Guide to Watches

Watches are extraordinary things. Feats of engineering you can strap to your wrist. Whether you choose mechanical or quartz, traditional or smart, your watch has an important role: It lets people know who you are. Even if that’s just a guy who wants to know the time without reaching into his pocket.

The Last American Watchmaker The greatest timepieces in the world come from Switzerland. And Amish Country. By Josh Ozersky

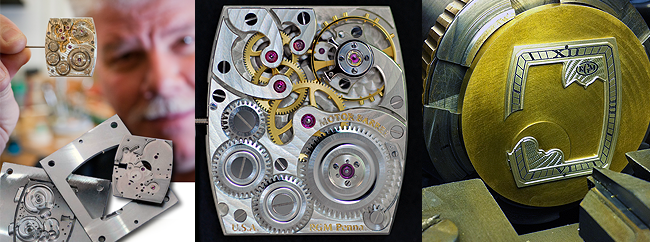

On the corner of a nondescript block in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, is a bank, or what used to be a bank. Now it is the home of Roland G. Murphy Watch Company, the country’s only true independent elite watchmaker. Inside, Murphy’s son-in-law, Adam Robertson, is bent over an old watchmaker’s drill press that looks like it was made during the Korean War. He uses an abrasive bit to create burnished, circular perlage on the underside of the main plate of the watch movement. He is focused and unmoving, his attention riveted to the plate, whose decoration no one will ever see. Later he’ll hand-polish the bevels of the screw holes on the tiny bridge that holds the wheel-train gears in place.

High-end watchmaking has not, for the most part, always been something you find in Amish country. Or, for that matter, in the United States. Typically, if you go looking for horological greatness, the kind of virtuosic craftsmanship associated with the greatest watchmakers, you go to Switzerland. If you are looking for scrapple, you go to Pennsylvania. But Murphy, the 53-year old owner and sole proprietor of the watchmaking company that bears his name, is the exception. Like some of the small European companies directed by a single watchmaker, RGM makes fewer than 300 watches a year. In contrast, the brands worshipped by most enthusiasts – Patek Philippe or Vacheron Constantin – produce tens of thousands a year. Rolex produces 2,000 a Of course, Rolex doesn’t operate in a space that looks more like an Elks Lodge than a watch manufacturer, with a collection of vintage cameras filling shelf after shelf, along with various other mementos. But then Murphy himself doesn’t fit the bill of a classic watchmaker. Burly, and with a thick head of salt-and-pepper hair and a bushy moustache to match, he looks more like a Pop Warner football coach. Like most watchmakers, he started out doing repairs, and found himself drawn to the silent, obsessive work of creating tiny universes of absolute order. After a few years of working on clocks, he found his way to Switzerland, where he made the horological equivalent of the big leagues: training at the Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Education Program, the Swiss watch industry’s official certification program in Neuchâtel. Not long afterward Murphy landed at Hamilton Watch Company, where he eventually rose to an executive development position.

Hamilton, it ought to be noted, is a famous American watch brand. But the dirty secret of nearly all American watch brands, Murphy’s excepted, is that they are either owned by the Swatch Group outright or utilize movements built and exported by one of its subsidiaries. Most of the American watch companies you’ve heard about are using Swiss movements and Chinese casings. And none even tries to produce the kind of arcane complications – a whirling tourbillon that compensates for gravity, say, or a precision moon-phase subdial – associated with the Patek Philippes and Jaeger-LeCoultres of the world. RGM makes what are by far the most intricate and ambitious timepieces produced in the United States. But they aren’t just clones of Swiss watches either. They’re inspired by the tough, durable railroad watches of industrial America. The paradox, of course, is that this rugged practicality is actually pure poetry. A $40 Casio G-Shock keeps more accurate time than a Breguet; a hot-pink Swatch a fourth-grader wears in the pool is more reliable than a watch that costs more than her home. When you think about it, there’s no reason for anyone to create in-house movements for an American watch. Murphy’s quixotic commitment to craftsmanship has no value to anyone but an equally idealistic buyer. Nowhere is this clearer than in Murphy’s masterpiece, the Pennsylvania Tourbillon. A mechanical watch, no matter how perfectly made, is affected slightly by gravity. The rhythm of its escapement, the part of the movement that regulates timekeeping, varies slightly based on how the watch is positioned. Not that anybody other than watchmakers would care or even notice. But the gravity problem stymied them, and so in 1801, Abraham-Louis Breguet patented a rotating cage to suspend the escapement, freeing it from the effects of gravity. Manufacturing a tourbillon is incredibly hard, which is why almost nobody does it. It’s also why two or three guys doing it in a Pennsylvania bank building borders on the fantastic.

Two bridges hold the tourbillon cage in place. Murphy and his master watchmaker, Benoît Barbé, bore tiny holes in the bridges to mount the escape wheel, pallet, and balance. They friction-fit a gold ring inside each hole and a jewel inside each ring. The 90-degree angle of the drilling, the depth of the holes, and the ring-and-jewel fittings must be precise to ensure the perfect relative positioning of the parts. The slightest variation would ruin the mechanism.The completed tourbillon turns 360 degrees once per minute, driven by a tiny spring coiled around the central axis. All of this work, by the way, can only be done by hand. A few of the parts can be machined, but even those parts are usually made by equipment the two men created themselves.

Murphy doesn’t build watches for himself or his buyer. He builds for an ideal: that things should always be better than what’s necessary. “We don’t design on the limit,” Murphy says. “Think about the Brooklyn Bridge. How much weight do you think it had to bear when they built it? Some horse carriages? Some pedestrians? Today there are giant semi trucks going over it all day, and it supports that weight because it wasn’t designed to the limit. That’s something we take pride in.” And it’s something you won’t find anywhere else in America.